Insutanto numa, 2009

For Haname Jinchoge (Kumiko Aso) life is a bit, well, uneventful. While she pines for an unrequited love, now making a name for himself in Italy, her job as a magazine editor is in jeopardy due to a distinct lack of sales. Day by day she laments the gradual erosion of her existence, seeking comfort only through her nostalgic-fuelled addiction to ‘Milo Sludge’. Even her mother (Keiko Matsuzaka) seems only content with making fantastical claims about water sprites living in her garden, much to her daughter’s chagrin, and it’s not long before Haname decides to get rid of all her worldly possessions and begin a fresh start. Things are about to come to a head when one day Haname receives word that her mother has been hospitalized after plunging into a pond in a bid to catch a Kappa. During a police investigation a long-lost mailbox is uncovered from the accident site, wherein thousands of undelivered – mostly illegible – letters have been stored for decades. One such letter which has managed to survive, however, reveals that the father she thought she once knew was never actually her own; with her mother now in a comatose state, she must takes matters into her own hands and seek the truth.

Soon Haname tracks down the whereabouts of her real father: an eccentric antiques dealer now going by the name of “Light Bulb” (Morio Kazama). Somewhat perturbed by his appearance and hippy mannerisms, Haname decides not to reveal her identity to him, instead merely passing herself off as a distant relative. Each day she returns to Light Bulb’s curious shop and each day they seemingly draw closer through their shared interests. It’s here that Haname befriends an electrician named “Gas” (Ryo Kase), whom she soon has joining her on treasure hunts for other locals, which also spurs her to open up an antique shop all of her own. Life suddenly seems to be looking up for the young dreamer, until an opportunity is presented to her that may see everything come crashing down.

It’s impossible to go through Instant Swamp – Miki Satoshi’s sixth film – without thinking of the director’s second feature Turtles are Surprisingly Fast Swimmers; they’re practically joined at the hip in their telling of female protagonists down on their luck, who wonder what more life can possibly afford them past their presently mundane existence. With linked themes that softly satirize a fiercely superstitious and often complacent society and one’s taking risks in the pursuit of happiness, it may initially appear that this time around we’ve seen everything before. However, Satoshi continues to prove that he still has many more tricks up his sleeve, with a strong knack for characterisation and the ability to convey his messages without having to try all that hard.

As a story teller Miki Satoshi has rarely relied on deeply packed or even logical narratives to make his points clear, and with Instant Swamp opening on Haname’s words that life doesn’t quite work the same way that it does in the movies, he eschews the clichéd components that often lend themselves to more conventional tales of self-discovery, be they romantic, comedic or otherwise. There’s no sentimental button-pressing throughout a plot which harbours ordinarily serious issues, as here we have a director wanting to have fun first and foremost, embracing his unique brand of fairytale humour whilst retaining an overall sense of awareness in his depiction of human emotions and traditionalism. As with most of his films to date, Instant Swamp is all about the journey, working no differently with its mixture of charming and quirky characters to drive events forward. Though the feature clocks in at a slightly lengthy two hours, Satoshi maintains a solid enough pace and through his characters’ bizarre whims and philosophies – especially those central to Haname and Light Bulb – he ensures a constant air of unpredictability amidst some exceptionally refreshing forging of family bonds.

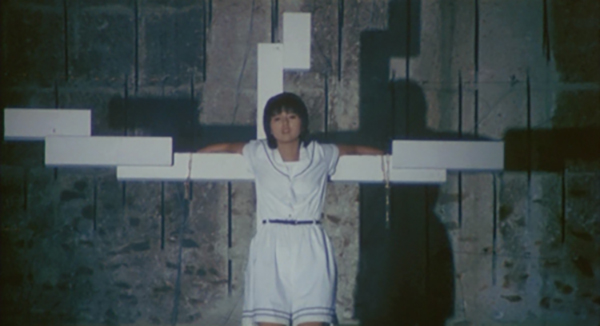

Instant Swamp is imbued with such unbridled energy and a genuine lust for life that it ensures the viewer leaves with a heavy smile. Miki Satoshi has assembled another cracking cast of familiar faces, and central to this is Kumiko Aso (returning after Satoshi’s Adrift in Tokyo) who puts in a spirited performance as our ditzy protagonist: scammed in life, though not wanting to be destroyed by the experience, Haname turns her misfortune into an opportunity which will lead on to one of the most surreally fantastic finales seen in recent years. Another triumph for a director who just cannot seem to do any wrong.